|

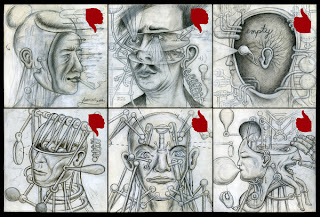

| Thinking Clearly About Personality Disorders |

SEOOKE.com: This weekend the Board of Trustees of the American Psychiatric Association

will vote on whether to adopt a new diagnostic system for some of the most

serious, and striking, syndromes in medicine: personality disorders.

Personality disorders occupy a troublesome niche in psychiatry.

The 10 recognized syndromes are fairly well represented on the self-help

shelves of bookstores and include such well-known types as narcissistic

personality disorder, avoidant personality disorder, as well as dependent and

histrionic personalities.

But when full-blown, the disorders are difficult to

characterize and treat, and doctors seldom do careful evaluations, missing or

downplaying behavior patterns that underlie problems like depression and

anxiety in millions of people.

The new proposal — part of the psychiatric

association’s effort of many years to update its influential diagnostic manual

— is intended to clarify these diagnoses and better integrate them into

clinical practice, to extend and improve treatment. The entire exercise has

forced psychiatrists to confront one of the field’s most elementary, yet still

unresolved, questions: What, exactly, is a personality problem?

Habits of Thought

Personality problems aren’t exactly new or hidden. They

play out in Greek mythology, from Narcissus to the sadistic Ares. They

percolate through biblical stories of madmen, compulsives and charismatics. They

are writ large across the 20th century, with its rogues’ gallery of

vainglorious, murderous dictators.

Yet it turns out that producing precise, lasting

definitions of extreme behavior patterns is exhausting work. It took more than

a decade of observing patients before the German psychiatrist Emil Kraepelin

could draw a clear line between psychotic disorders, like schizophrenia, and

mood problems, like depression or bipolar disorder.

Likewise, Freud spent years formulating his theories on

the origins of neurotic syndromes. And Freudian analysts were largely the ones

who, in the early decades of the last century, described people with the sort

of “confounded identities” that are now considered personality disorders.

Their problems were not periodic symptoms, like

moodiness or panic attacks, but issues rooted in longstanding habits of thought

and feeling — in who they were.

“A pedantic sense of order is typical of the compulsive

character,” wrote the Freudian analyst Wilhelm Reich in his 1933 book, “Character

Analysis,” a groundbreaking text. “In both big and small things, he lives his

life according to a preconceived, irrevocable pattern.”

Others coalesced too, most recognizable as extreme

forms of everyday types: the narcissist, with his fragile, grandiose

self-approval; the dependent, with her smothering clinginess; the histrionic,

always in the thick of some drama, desperate to be the center of attention.

In the late 1970s, Ted Millon, scientific director of

the Institute for Advanced Studies in Personology and Psychopathology, pulled

together the bulk of the work on personality disorders, most of it descriptive,

and turned it into a set of 10 standardized types for the American Psychiatric

Association’s third diagnostic manual. Published in 1980, it is a best seller

among mental health workers worldwide.

These diagnostic criteria held up well for years and

led to improved treatments for some people, like those with borderline

personality disorder. Borderline is characterized by an extreme neediness and

urges to harm oneself, often including thoughts of suicide. Many who seek help

for depression also turn out to have borderline patterns, making their mood

problems resistant to the usual therapies, like antidepressant drugs.

Today there are several approaches that can relieve

borderline symptoms and one that, in numerous studies, has reduced

hospitalizations and helped aid recovery: dialectical behavior therapy.

This progress notwithstanding, many in the field began

to argue that the diagnostic catalog needed a rewrite. For one thing, some of

the categories overlapped, and troubled people often got two or more

personality diagnoses. “Personality Disorder-Not Otherwise Specified,” a

catchall label meaning little more than “this person has problems” became the

most common of the diagnoses.

The assessment interviews can last hours, and

treatments for most of the disorders involve longer-term, specialized talk

therapy.

Resisting Simplification

The most central, memorable, and knowable element of

any person — personality — still defies any consensus.

A team of experts appointed by the psychiatric

association has worked for more than five years to find some unifying system of

diagnosis for personality problems.

The panel proposed a system based in part on a failure

to “develop a coherent sense of self or identity.” Later, the experts tied

elements of the disorders to distortions in basic traits.[nyt]

Post a Comment

1. Silahkan anda berkomentar dengan baik dan sopan.

2. Komentar yang anda berikan akan menjadi kemajuan blog ini.

3. Bagi yang mencari backlink silahkan komentarlah dan jangan spam..

4. Ada pertanyaan silahkan hubungi kami secara private.

5. Terima kasih atas kunjungannya.